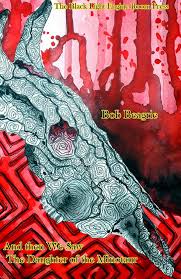

Tuesday Poem: And Then We Saw The Daughter of the Minotaur, Bob Beagrie

English poetry is blessed with fantastic poets whose work never makes the headlines. Bob Beagrie is one of them. His work has been translated into ten languages, yet his name is still less well known in the UK than it should be. I met Bob when I was the RLF Fellow at Teesside University, where he teaches creative writing. The breadth and depth of his work amazed me. His poetry is rooted in the oral, performable traditions of poetry and is often accompanied by music. Leasungspell (Smokestack 2016) is set in 7th century Northumbria and plays with Old English languages and dialect. It is 'the small tale of a nobody wandering alone through the Dark Ages', written along the faultlines where the new religion and the old magic collided, shattering linguistics and mythologies.

His work is often political. Civil Insolencies (Smokestack 2019), whose publication coincided with the Brexit debate, has its roots in the literature of the Levellers and the Royalists at the time of the English Civil War in the 17th century. It tells the story of the Battle of Guisborough, which becomes a micro-canvas where the social inequalities and injustices that drove the Civil War are played out. The parallels with twenty-first century Britain are clear.

His latest work And Then We Saw the Daughter of the Minotaur, is a sonnet sequence which is much more personal, referencing the painting by surrealist Leonora Carrington.

The sequence was written after Bob's far-too-young wife suffered a brain hemorrhage, which could have killed her, the poems are moving and compelling, from the initial dash to collect her from a railway station, to the final post-hospital reunion in the hotel where they had their honeymoon. First, he has to navigate the labyrinths of city road networks, low on fuel and his phone out of charge.

'It's about an hour's drive to York.I know the route of the tarmac maze

by heart, each intersection, slip road,

roundabout, wind and fork, clocked as I pass

in the early dark. . .'

Bob's wife has collapsed at a railway station and he brings her home where it becomes clear that she is seriously ill. She collapses again and Bob rings 999 and finds himself caught in a dark underground world of fear and grief that seems to have no way out.

The arched ceiling is adrift with grazing clouds

supported by rows of Corinthian columns,

it's surprisingly warm in the bowels of the earth.

The tunnels around us squeeze all sound

to a nugget of hard jet. I hold her hand

as we scramble over rubble, bones, leave

footprints in dust. I think the sea is above us.

I think I can hear its pulse - the ever-grind-

and-scrape of itself on its bed, restless, insatiable,

nibbling on the roots of lost cities, foregone

civilisations, there are marks on the walls

of these chambers: glyphs, pictograms, graffiti -

Please don't leave me here please don't leave

me please don't leave please don't please . . .

At the hospital, in a surreal landscape neither of them recognise, they come face to face with the female doctor, who they recognise as the Daughter of the Minotaur. She diagnoses a bleed on the brain. "Is she dying?" I enquire in silence./ "Can you name one person who isn't?" A surgeon, in the person of Theseus, expertly slays the monster lurking in the labyrinths of his wife's brain, while the poet paces rooms 'mapping their meridians,/ hang my breath on the mast like an ensign . . . the sun drowning in the insatiable sea,' and finally goes home, 'repeating the question I cannot be sure of;/ "Did I glance back as I left the labyrinth?" Finally his wife escapes, assisted by the Minotaur's daughter. She is in recovery, 'headaches, brain fatigue, but she/ is walking now, remembering . . .'

'Tomorrow we plan to drive down to the beachbeyond the field of bullocks with sad coal eyes,

climb over the dunes to spend some time with

the shifting permanence of sand, sea, wind.'

Thank you for this introduction. I'm going to look for his work.

ReplyDelete