Tuesday Poem: Afghan women's poetry

|

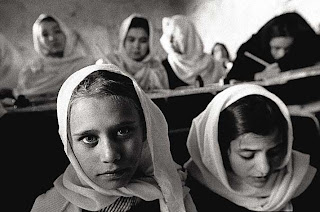

| Copyright Seamus Murphy, Poetry Foundation |

You sold me to an old man, father.

May God destroy your home, I was your daughter.

Making love to an old man

is like fucking a shriveled cornstalk blackened by mold.

I call. You’re stone.

One day you’ll look and find I’m gone.

These were translated by, and are copyright to, Eliza Griswold, who has just written a fine article for the Poetry Foundation on the subject of Landays and Afghan women. She explains that . .

'Landays began among nomads and farmers. They were shared around a fire, sung after a day in the fields or at a wedding. More than three decades of war has diluted a culture, as well as displaced millions of people who can’t return safely to their villages. Conflict has also contributed to globalization. Now people share landays virtually via the internet, Facebook, text messages, and the radio. It’s not only the subject matter that makes them risqué. Landays are mostly sung, and singing is linked to licentiousness in the Afghan consciousness. Women singers are viewed as prostitutes. Women get around this by singing in secret — in front of only close family or, say, a harmless-looking foreign woman. Usually in a village or a family one woman is more skilled at singing landays than others, yet men have no idea who she is. Much of an Afghan woman’s life involves a cloak-and-dagger dance around honor — a gap between who she seems to be and who she is.'

If you would like to read more and see the fabulous photographs of Seamus Murphy, this is the link.

Eliza Griswold, a Guggenheim fellow, is the author of a collection of poems, Wideawake Field (2007) and a non-fiction book, The Tenth Parallel: Dispatches from the Fault-line between Christianity and Islam (2010), which was awarded the Anthony J. Lukas Prize in non-fiction. Both books are published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. She has had the pleasure to work with Seamus Murphy in Africa and Asia for more than a decade. She lives in New York City.

Seamus Murphy began photographing Afghanistan in 1994, leading to the book A Darkness Visible: Afghanistan (Saqi Books, 2008), a focus on the Afghan people through the turbulent years 1994–2007. His film of those experiences was nominated for a 2012 Emmy Award and received the 2012 Liberty in Media Prize. Murphy undertook three trips to Syria in 2012. His multimedia film Syrian Spring was nominated for a Prix Bayeux-Calvados for War Reporting. “Photography is part history, part magic,” says Murphy.

All Copyright The Poetry Foundation 2013

For more Tuesday Poems, please visit the Tuesday Poem Hub, and check out what everyone else is posting. There's a rich mix of poetry from around the world. This week the featured poem is by Rachel O'Neill.

Thanks for posting this Kathleen. It's wonderful that these women have a vehicle in which to express their feelings but shocking that they have to go through what they do. It's horribly humbling.

ReplyDeleteAmazng and terrible, cheers for posting.

ReplyDeletethank you Helen and AJ - yes, it affects me the same way, both horror and admiration. Such suffering seems terrible in a supposedly humanitarian world.

ReplyDeleteExcellent post. Thank you.

ReplyDelete