What Happened to Sally?

I first met the woman I'll call Sally when I was twenty, newly out of England, my first time on a plane. I was sitting in the lounge at Beirut airport, waiting out a twelve-hour transit, and I had a baby on my lap. Beirut airport was a confusing experience. I was fascinated by crowds of men talking staccato Arabic, some of the men wearing a European waistcoat over their long white robes, with a red Fez on their heads. There were women in black veils, the occasional Europeans - confident women in designer dresses with furs carried casually over their arms; the men in three-piece suits, followed by Arab boys with trolleys of luggage.

I became aware of a very tall woman with long blonde hair in a man's dishdashieh, a wide gold collar around her neck. She was striding up and down the rows of seats brandishing what looked like a very expensive camera taking photographs of the crowds. Sometimes she crouched down to get a better shot. She stopped in front of me and asked if she could photograph my small son, who was just beginning to toddle. Her accent was American - the full-on southern drawl, and her manner was bold almost to the point of rudeness. Feeling lost and vulnerable in a foreign country, I envied her assurance.

'What are you doing here?' she asked. I explained that I was flying out to the Gulf States to join a husband I hadn't seen for six months and had a long stopover. 'Then I must show you Beirut,' she said, impulsively. 'If you've never been here before you must see the most amazing city in the world.' I was commandeered, all protests silenced, and taken out of the airport, plane ticket and passport waved through by an airport official who seemed quite familiar with this force of nature who told me her name was Sally.

|

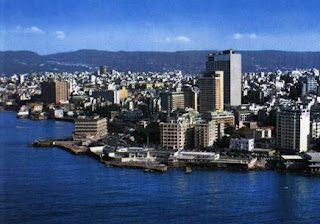

| Beirut in the 1970s before the war |

|

| Beirut - after the war |

She was in Beirut to take a series of photos for the National Geographic, she explained as she hailed an elderly Toyota taxi driven by an equally elderly man whose head was swathed in white, smoking a long cigarette out of the window. It was dark, but the city was ablaze with lights. She kept giving the driver instructions in a mixture of French and Arabic. At the Phoenicia Hotel he was ordered to wait while we went into the bar, where she bought me a glass of bourbon and exchanged banter with the barman who gave my son some sweets. Sally began to tell me details about her life. She'd been living in Venice, in a ground-floor apartment paid for by her Italian lover. But she'd had to leave after an exceptionally high Aqua Alta. She was a professional photographer and journalist - Vogue, Time Magazine, Geographic - and was now writing her first novel. She was a writer - everything I was trying to be. Sally seemed fascinated by my son, now asleep in my arms, and told me that she had a nine-year-old daughter who lived with her grandmother in Milwaukee.

Then it was back to the taxi and around the city, the corniche, where the bay stretched out into the Mediterranean, illuminated by the moon. We drove along the boulevards with their nightclubs and elegant Napoleonic facades, paused to look at the main square with its fountains and palm trees. Beirut, before it was shelled into rubble was one of the most beautiful cities. the meeting place, Sally told me, of European and Middle Eastern culture. 'But you just have to see the Roman temples at Baalbek by moonlight,' Sally said, made more enthusiastic by the bourbons she'd downed at the Phoenicia.

|

| Roman Temples at Baalbek |

She gave instructions to the taxi driver who stopped suddenly in the middle of the street and demanded American dollars in advance for such a trip. Sally didn't have any and she seemed surprised to find that I didn't have any, not so much as a dinar of foreign currency on me, since I hadn't been expecting to need any. So we didn't go. But Sally pointed out to me the ring of mountains that edged the horizon, the moon just catching odd patches of white snow on their peaks.

|

| The Phoenicia Hotel |

'You must come back and see it all!' she said. The sky was lightening in the east when she dropped me back at the airport. I put two pound notes I found in my pocket into the driver's hand as we went back inside and hoped it would be enough of a contribution.

I thought I would never see the woman who had erupted into my life like a volcano, again. I flew to Dubai on the morning flight and then took a DC3 to Abu Dhabi where the plane landed on the beach. A man was waiting for me, a stranger I didn't recognise, bearded, tanned to a shade of mahogany. Our son shrank from his father and wouldn't go near him for days. We were staying in a small room in a half-built hotel near the seafront. There was only space to walk round the bed we had to share with our son. Electricity depended on an old generator; there was no air conditioning and water only for an hour or so twice a day, or when the tanker arrived from the Buraimi oasis.

|

| Camels in the Desert |

We were invited to a small reception at the Embassy. I was one of only six European women in the Sheikhdom so most of the guests were men, very smart in their white tropical evening jackets. But there, half a head taller than anyone in the room, was Sally, glass in hand, this time wearing a very short blue silk shift she told everyone was Christian Dior and had been a gift from a lover in Paris. She pounced on me, found out where I was staying and became a frequent visitor. Sally said she was still working for the Geographic, living in a room behind the Suekh for the 'genuine experience'.

When we moved out of the hotel into a prefabricated house shipped from Denmark, complete with contents, she became an even more frequent visitor. My house had air conditioning, so where better to sit out the afternoon heat than my sitting room. She would stay for hours, talking mainly about herself and the novel she was writing. Her agent in the US was very excited by the idea, she said. It was going to be about this young woman who finds herself adrift in the Arab world. I began to wonder if I was being used for copy.

By now I was pregnant again and finding the climate exhausting. I longed to spend the afternoon siesta in my air-conditioned bedroom. I began to avoid Sally. I locked my front door and went to bed, pretending not to hear the car, the knocking on the fly screen. 'Why are you hiding from me?' she asked one day when we met in the Suekh. I lied and said I wasn't, but she knew.

One day, when my son was at nursery, full of remorse, I drove into the group of houses behind the Suekh to try to find out where she was staying. I asked a small boy, in my rapidly improving Arabic, where the American woman lived. He pointed to a small white building and made a rude gesture. A big Cadillac was parked outside with the gold, crossed swords of the royal family on the number plate. I went away and came back a few days later.

She asked me in, grudgingly, making apologies for her way of living. 'It's all very simple,' she said, waving her arm round the single, white-washed room. 'There's no distractions.' She offered me lukewarm Coca-Cola and sat down on a rug on the floor, gesturing me to sit down opposite her. Her typewriter sat on a tin trunk that seemed to be the only piece of furniture she had. The floor was loose sand, a camping stove stood in a corner, pots and pans and carrier bags of food were hung on hooks on the walls - to keep them away from the rats, she said in a jokey way. 'And the cockroaches.'

'What do you do for the bathroom?' I asked. She showed me a corner of the yard outside, which had a bamboo screen around it. Inside, a hole in the ground buzzed with flies. There was a barrel of water and a plastic scoop that served as a shower. I was shocked. I was also worried about her. Sometimes when I saw her she was drowsy and spaced out, and I had begun to suspect that she was taking drugs. Hashish was everywhere in the Suekh, and so was opium. I wondered if this was one of the reasons that we never met Sally at parties anymore - the European community had closed ranks against her. She was unpredictable, charming when she was in the mood but riotous when she'd had a few drinks and liable to cause scenes. My husband wanted me to cut the connection. 'Everyone else has,' he said. 'She's bad news.' But I couldn't. I was beginning to write my own novel, and she was a character in it.

When my daughter was born in the local hospital, Sally gave me a framed photograph and signed it 'To a fellow traveller and a faithful friend.'

|

Then one day she came round to the house very agitated. The Sheikh had refused to sponsor her for another residence visa. She had to leave the country in two days' time. Would I keep her belongings for her until she had somewhere to stay and could send for them? Of course, I said. The next day she brought the tin trunk which contained, I was told, the Dior dress, the typewriter and the draft of her novel. 'I've sent the original to my agent,' she said. She had sold the gold necklace to pay for a flight to India.

I never saw her again. When we left Abu Dhabi I gave her trunk to the American Consul to keep for her. Later, back in England, a letter arrived, forwarded from Abu Dhabi by my husband's firm. It was already three weeks old. Would I wire her some money? Sally wrote. Urgently? She was destitute. Her cameras had been stolen and she was begging outside the airport in Delhi. Her mother had cut her off. I was her last hope. 'I need food,' she wrote, 'and a plane ticket out of here.'

I had no money of my own. I showed the letter to my husband, who refused to send her anything. 'The US Embassy will help her,' he said. 'It's her own fault she's in such a state.'

And that was the last contact I had with Sally - though I always hoped to find some trace of her in magazines, publishing news, the Geographic; but she had vanished. I'm still haunted by her.

Comments

Post a Comment