The 'Trailing' Wife: International Women's Day

By the time my third child was born at the age of 28, I'd moved 29 times, visited 18 countries and lived in 4 of them. The logistics of packing and moving, and establishing a functional family life wherever we were, was always left to me. It was what women did. During ten years of marriage I'd lived in hotels, B&Bs, with relatives, in rat-infested flats, cockroach-ridden Arabian villas, African bungalows, and an assortment of rented, furnished accommodation. I was what was known as a 'trailing' wife. I followed my husband wherever he went, dragging the children with me. They lived it too and there were some very happy times.

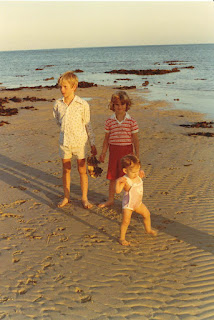

A beach in the United Arab Emirates

But there were other times too. By the time the older children were 10 they had been to 7 different schools. We lived out of suitcases and steamer trunks. we coped with military coups, power cuts in 48 degrees of heat, economic collapse, and accident and illness in third world countries without proper medical facilities. It left its mark on all of us, physically and mentally. But it made us resilient. When I was growing up on a remote hill farm in the Lake District, I never saw myself bribing my way onto an aeroplane during a coup in an African state dissolving into chaos. This is an extract from a memoir:

The peaceful situation after the first military coup didn’t last. Within months there was a counter-coup, a rebellion by rival military officers, and this time not so benign. My husband, Chris, was in Nigeria, negotiating another contract and unable to return when the country’s borders were abruptly closed. I realised something had happened when my steward, Richard, didn’t come to work, so I turned on the radio to hear the familiar martial music. The telephone network was down, so I walked down to a neighbour’s house to be told that soldiers were looting the town and I should go home and lock myself in. At lunchtime Paul, the garden boy, arrived and hammered on the sliding door. I let him in. He looked pale and was carrying two machetes. He gave one to me. ‘The soldiers are coming,’ he said, ‘you must make everything safe.’ We made sure every window was closed, the curtains drawn, every door locked and furniture moved against them. Paul sat inside the kitchen door, machete in hand, and I got the children into their bedroom, barricaded the door and crouched on the floor, with the other machete, knowing that I might have to use it. Then the soldiers came, running round the house, banging on the walls, running their rifle butts over the bars, firing the guns into the air, shouting ‘Yi! Yi! Yi!’. I pushed the children under the bed and shielded them with my body. And then the soldiers were gone, but we could hear the gunfire out in the cantonments. Some of the empty houses were ransacked.

The coup failed, but it was two days before Chris could get back from Lagos. The schools and shops were closed for a week. Even though things began to go back to normal our lives changed very quickly. There were military roadblocks on every road, the banks didn’t always have money when you went in to withdraw cash. The airports were crowded with foreign nationals returning home. It was announced that, because of the corruption of the previous government, the country was bankrupt. The cedi ceased to be traded on the international money exchanges. The IMF proposed stringent terms for a loan, which the military council refused. Imported goods no longer arrived. Medicines, including anti-malarial drugs, were unobtainable and, overnight, essential food vanished from the supermarket shelves. Local fruit and vegetables were still on sale in the market, though prices doubled, but all the imported meat, cheese and other staple foods, cereal, dairy products, sugar, flour, rice, coffee and tea, as well as washing and hygiene products became a memory.

Riots in Ghana

Hotels and restaurants closed. Only the restaurant belonging to the Minister of the Interior, who had a Swiss wife, remained open for anyone who could afford the prices. My diary records being taken out to dinner by a client and stealing the sugar lumps out of the bowl on the table. On April 4th the car broke down, and a month later I wrote, ‘Still no car for lack of spare parts. . . we are without indefinitely’. But the flame trees were vibrant with red plumes and the orchid tree was a mass of creamy bloom. Long-tailed Whyddah birds performed cheerful acrobatics on the telephone wires every morning. The government brought in rationing for essentials and a flourishing black market sprang up for goods smuggled in from neighbouring Togo and Sierre Leone.

Anyone paid in hard currency could drive over the border, fill up their car boot at Carrrefour and drive back, bribing the border guards with cigarettes and whisky. Because we were paid in local currency we didn’t have that option, and inflation meant that Chris’s salary halved in value overnight. He employed a boy at the office whose job it was to scour the town for food. The Foreign Office advised all those who could to leave. Chris still had six months to run on his contract, which we were expected to fulfill, before the firm would pay for a flight back to the UK. I could have left with the children, but there was no home to go to and no money to pay for us to live anywhere but Ghana. I realised that I was totally dependent on my husband.

Travelling children: a railway station somewhere in China

Pets were being abandoned by fleeing Europeans. I went with a friend to rescue two cats from a neighbour’s house, and we acquired a guard dog from another. He was a strange mixture of bush dog and long-haired English Sheepdog. The children loved him but, we discovered too late, that he’d been trained to be very aggressive with people whose skin was not white. As we had many Ghanaian friends, this was embarrassing. It was also difficult for the staff. I had to lock Watson on the veranda before my steward, Richard, would clean the house. But there was no doubt that I felt safer. No policeman was going to hi-jack my car with Watson on the back seat; and any thief was going to think twice about breaking into the house with him there. At the British club, the pool began to turn an unhealthy shade of green as chlorine supplies failed to arrive. The steamer chairs were empty and, when you ordered a drink at the bar, you first had to ask what they had behind the counter. Very few Europeans were left. We huddled together like survivors of a shipwreck.

The Centre of Accra

The next attempted coup happened a few months later as the military officers argued amongst themselves. One of the Colonels wanted to set up an interim civilian administration pending democratic elections. By coincidence, Chris was again absent. An Italian friend, Piero, had planned a trip up-country to check on his timber suppliers and had offered to take Chris, and my son David, with him. They intended to go to the far north, on the border with Burkina Faso, where the land turned into savannah and there was a lot of wildlife, giraffes, elephants and leopards. This was a Boys’ Own adventure. Piero argued that his car wasn’t big enough to take me and two-year-old Peta as well. Chris thought she wasn’t old enough for such a rough expedition anyway.

Two days after they left I woke up and found that none of the staff had come to work. I gave Peta her breakfast, listening to the martial music on the radio, and recognised the familiar sound of gunfire in the distance. Surrounded now by empty houses, remembering the last time, I felt very afraid. I made up my mind to leave if I could. There had been roadblocks on the main roads since the previous coup, so driving out wasn’t an option, even if I’d had enough fuel and a reliable car. The telephone line was still connected, so I rang the airport and was told it was open for internal flights, though the borders had been closed. I grabbed a suitcase, threw some clothes into it, ransacked the house for whatever money I could find, let the dog out into the garden, put my daughter into the car and drove to the airport using only the back streets.

At the airport, the departure lounge was rammed with people. I asked the ticket clerk what planes were leaving and was told there was only one flight for Kumasi in the north, already boarding.

‘I would like a ticket please,’ I said.

‘But it is full madam,’ he replied.

I put some money on the desk. ‘I have to be on that flight,’ I said. ‘Please?’ Peta had begun to cry and I picked her up. I put some more money on the desk and then some more, feeling suddenly quite desperate. Eventually he took the cash and reluctantly issued me with a ticket.

The plane was a WWII Douglas DC 3. There were holes in the fuselage. The pilot, a veteran Australian with blood-shot eyes, was going through the cabin, redistributing the passengers to balance the weight. He kept counting and re-counting them. I kept very quiet, sitting on one of the crew seats at the back with Peta on my lap. He asked two African women for their tickets, which were in order, but didn’t check mine. Still puzzled, he closed the doors and soon we were taxiing out to the runway. I felt nauseous with relief. As we skimmed the rain forest, I could see the tops of the kapok trees through the floor, but we skidded safely down the runway in Kumasi.

I had no plan beyond getting out of Accra and knew no one in the north. After we landed, I shared a cigarette and a can of warm Fanta with the pilot on the grass beside the runway. He was curious to know what I was doing there and, when I told him the story, he suggested I go into town and enquire about the government guest house. I remembered that there was a branch of the firm’s bank, Standard and Chartered, in Kumasi, so I took a taxi there. The manager, a smiling man called Joe, came to the reception desk and said, ‘I’ve just seen your husband!’ Chris, David and Piero, were staying at the guest house on the edge of town.

We spent the night in the guest house, discussing what we were going to do. Peta and I could have stayed there for a few more days before returning to Accra, but the situation was so unstable, we couldn’t be sure that Kumasi wouldn’t be affected. I was also reluctant to go back on my own. In the end it was decided that I should go with them. After some juggling of luggage, fuel cans and an improvised roof rack, we all crammed into Piero’s old Peugeot and headed north for Bolgatanga and Burkina Faso.

Comments

Post a Comment