Jessie Kesson: The White Bird Passes

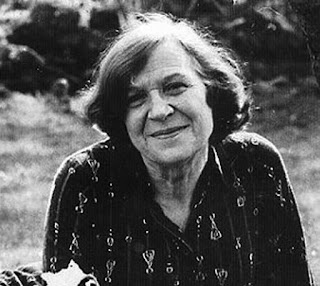

I was recently introduced to the work of Scottish author Jessie Kesson. She was a novelist, poet and playwright who did a lot of work for the BBC, but also a nature writer and friend of Nan Shepherd. Jessie was the illegitimate child of a woman who lived in the tenements of Glasgow and, through poverty, drifted into casual prostitution. Jessie was taken into care and brought up in orphanages while her mother died slowly and painfully of syphilis. Although intellectually brilliant, the ‘training schools’ of Scotland only equipped girls for a life in service. Instead of going to university, as she wished, Jessie worked as a servant until she met her husband, an agricultural worker. For the first decade of her married life, Jessie was a ‘cottar wife’ – working on the farms alongside her husband, living in ‘tied’ houses, with no security and very little money.

The Glasgow Tenements painted by Joan Eardley

Jessie became a published writer, encouraged by Nan Shepherd, a stranger she met on a train. Critics talked about ‘Kesson’s consummate ability to catch the moment passing; that transitional, trembling point of awareness of life as painful yet delightful, dangerous yet desired . . . As always in Kesson, there is that sense of a pool of light beyond which the darkness lowers’. (Books in Scotland) Her account of life in the tenements reminds me very much of the paintings of Joan Eardley.

Jessie was a protégé of Carmen Callil, published by Virago. But it was as a broadcaster that she was best known. I’ve just discovered her novel, The White Bird Passes, a fictional account of growing up in the tenements and being taken into care. It’s a novel written by a poet and playwright. The descriptions of place are stunning, the characters leap off the page and the dialogue is so brilliant you can close your eyes and hear them talking to you. No wonder that it was turned into a film.

Towards the end of the book, the young girl, told that she must leave the shelter of the orphanage, stands on the edge of the wild land, listening to the wind. She’s full of passion and wild emotions she doesn’t know how to handle.

‘. . . the aloneness of the night was beyond the bearing of the land itself. It caught you, the land did, if you walked it at night. Held you hostage. Clamped and small within its own immensity, and cast all the burden ot its own aloneness upon you. The wind had begun to threaten the air. Passionately she had longed for the wind to come. To blow herself and the landscape sky high into movement and coherence again. Almost she had been aware of the wind’s near fierceness. Ready to plunge the furious hillside burns down into Cladda river. To hurl the straws over all the dykes. To toss the chaff into the eyes of protesting people, bending before it, flapping in their clothes like scarecrows. To sting the trees in Carron wood into hissing rebellion.’

How sad that such a fantastic novel has almost vanished from view. I’m grateful that it has been re-issued, and I’ve now found others, which are on my TBR list.

Comments

Post a Comment