The Guilty Pleasures of Cosy Crime

Okay, so I like Cosy Crime as much as I like Nordic Noir. I admit it. There’s only so much psychopathy I can take. Alone in the Mill, in the middle of the night, I turn to Cosy Crime, where everybody (except the victim of course) ends up safe and sound and nobody mourns the murdered soul because obviously they had it coming to them. Anything else is just a little too real and likely to render me sleepless and paranoid about every tiny noise.

I’ve always loved solving mysteries, in the way that I love puzzles of any kind, so crime fiction has been an addiction since childhood. (Remember Nancy Drew?) Agatha Christie was on the bookshelves at home, but I always found her books rather cold and clinical. My mother had the Father Brown mysteries by G.K. Chesterton and, although I didn’t like them as much as she did, I liked the idea of natural justice that they put forward. Father Brown’s solution to the case didn’t always involve the police – but the punishment always fitted the crime.

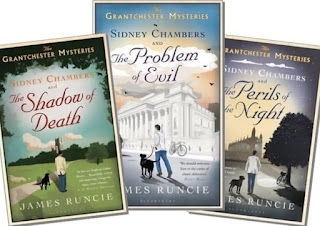

James Runcie’s Grantchester mysteries seem to follow this tradition. The 32 year old hero, Canon Stephen Chambers, has a privileged position as an Anglican priest – people tell him things and feel that he has a right to probe their consciences and ask awkward questions about their private lives. The stories begin in 1953 and continue through to 1977, so we see the character develop.

I prefer the Stephen Chambers of the books to the TV detective priest, because the books are more literary (he’s very well read is our Stephen) and there is more moral subtlety. I don’t mind his religious dilemmas, even though I’m an atheist, because he is much more of a Doubting Thomas than Father Brown ever was. Less smug too, and very human. The TV adaptations make Chambers far too black and white. I watched a couple of them and then didn’t bother to watch again. The books are more ‘real’.

What I do like about the stories is what they reveal of village life with its hierarchies, jealousies and snobberies – the gossip and the secrets that are never really secret. And they are very well crafted- Runcie is a formidable writer, not surprising given his personal history. He is the son of a former Archbishop of Canterbury, born in Cambridge, so he writes of what he knows. He is also a film maker, novelist, TV producer and playwright, and Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. His CV is awesome.

All right, so they are a bit cosy – but everyone has their comfort read. And I was once married to a clergyman’s son, so it takes me back into a world of baffling parochial and diocesan intrigue and the splitting of microscopic moral hairs. My late father-in-law (St John's College, Oxford) also read the grace in Latin and, as he was a widower, the single women of his congregation were given to throwing themselves at the vestry door (metaphorically speaking). There was a great deal of material for fiction. I can see where James Runcie gets his plots!

I’ve always loved solving mysteries, in the way that I love puzzles of any kind, so crime fiction has been an addiction since childhood. (Remember Nancy Drew?) Agatha Christie was on the bookshelves at home, but I always found her books rather cold and clinical. My mother had the Father Brown mysteries by G.K. Chesterton and, although I didn’t like them as much as she did, I liked the idea of natural justice that they put forward. Father Brown’s solution to the case didn’t always involve the police – but the punishment always fitted the crime.

James Runcie’s Grantchester mysteries seem to follow this tradition. The 32 year old hero, Canon Stephen Chambers, has a privileged position as an Anglican priest – people tell him things and feel that he has a right to probe their consciences and ask awkward questions about their private lives. The stories begin in 1953 and continue through to 1977, so we see the character develop.

I prefer the Stephen Chambers of the books to the TV detective priest, because the books are more literary (he’s very well read is our Stephen) and there is more moral subtlety. I don’t mind his religious dilemmas, even though I’m an atheist, because he is much more of a Doubting Thomas than Father Brown ever was. Less smug too, and very human. The TV adaptations make Chambers far too black and white. I watched a couple of them and then didn’t bother to watch again. The books are more ‘real’.

What I do like about the stories is what they reveal of village life with its hierarchies, jealousies and snobberies – the gossip and the secrets that are never really secret. And they are very well crafted- Runcie is a formidable writer, not surprising given his personal history. He is the son of a former Archbishop of Canterbury, born in Cambridge, so he writes of what he knows. He is also a film maker, novelist, TV producer and playwright, and Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. His CV is awesome.

|

| James Runcie - a kind of southern Alan Bennett |

Comments

Post a Comment