Tuesday Poem: Norman MacCaig - Aunt Julia

Aunt Julia spoke Gaelic

very loud and very fast.

I could not answer her —

I could not understand her.

She wore men's boots

when she wore any.

— I can see her strong foot,

stained with peat,

paddling with the treadle of the spinning-wheel

while her right hand drew yarn

marvellously out of the air.

Hers was the only house

where I've lain at night

in the absolute darkness

of a box bed, listening to

crickets being friendly.

She was buckets

and water flouncing into them.

She was winds pouring wetly

round house-ends.

She was brown eggs, black skirts

and a keeper of threepennybits

in a teapot.

Aunt Julia spoke Gaelic

very loud and very fast.

By the time I had learned

a little, she lay

silenced in the absolute black

of a sandy grave

at Luskentyre. But I hear her still, welcoming me

with a seagull's voice

across a hundred yards

of peatscrapes and lazybeds

and getting angry, getting angry

with so many questions

unanswered.

© the estate of Norman MacCaig

from The Scottish Poetry Library

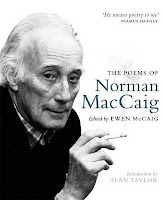

This week is the twentieth anniversary of the death of Norman MacCaig, one of Scotland's foremost poets, so I thought it was fitting to have one of his poems to celebrate the life and work of a poet whose poetry is gradually slipping out of view beyond the Scottish borders. 'Aunt Julia' is one of my favourites partly because it depicts such a wonderful character, (I can see her strong foot/stained with peat) and partly because it identifies one of the most tragic aspects of Scottish history.

Norman MacCaig's Aunt Julia, like his mother, came from the Isle of Harris and had Gaelic as a first language. Norman, like the majority of his generation, spoke English. It is one of the clearest examples of the cultural colonialism practised within the British Empire. Stamping out the language was a deliberate attempt to wipe out the culture and with it the connections to communities and landscapes. It has left a huge gap in people's lives that still has social implications.

One of the readers who nominated Norman's poem for the Poetry Archive commented that - "I too have often felt isolated from my own heritage. As I don't speak the native language of my homeland, I can only learn about the origins of my culture from what I can see. Language is so integral to culture that it almost impossible to understand a culture without understanding the language – especially when that culture is based upon an oral tradition."

Gordon Brown once quoted from one of Norman's poems 'Praise of a Man' in a eulogy he gave for a friend. The last lines could serve equally as a eulogy for the poet.

'He's gone:

but you can see

his tracks still, in the snow of the world.'

Norman MacCaig; 1910 -1996

Scottish Poetry Library

very loud and very fast.

I could not answer her —

I could not understand her.

She wore men's boots

when she wore any.

— I can see her strong foot,

stained with peat,

paddling with the treadle of the spinning-wheel

while her right hand drew yarn

marvellously out of the air.

Hers was the only house

where I've lain at night

in the absolute darkness

of a box bed, listening to

crickets being friendly.

She was buckets

and water flouncing into them.

She was winds pouring wetly

round house-ends.

She was brown eggs, black skirts

and a keeper of threepennybits

in a teapot.

Aunt Julia spoke Gaelic

very loud and very fast.

By the time I had learned

a little, she lay

silenced in the absolute black

of a sandy grave

at Luskentyre. But I hear her still, welcoming me

with a seagull's voice

across a hundred yards

of peatscrapes and lazybeds

and getting angry, getting angry

with so many questions

unanswered.

© the estate of Norman MacCaig

from The Scottish Poetry Library

This week is the twentieth anniversary of the death of Norman MacCaig, one of Scotland's foremost poets, so I thought it was fitting to have one of his poems to celebrate the life and work of a poet whose poetry is gradually slipping out of view beyond the Scottish borders. 'Aunt Julia' is one of my favourites partly because it depicts such a wonderful character, (I can see her strong foot/stained with peat) and partly because it identifies one of the most tragic aspects of Scottish history.

Norman MacCaig's Aunt Julia, like his mother, came from the Isle of Harris and had Gaelic as a first language. Norman, like the majority of his generation, spoke English. It is one of the clearest examples of the cultural colonialism practised within the British Empire. Stamping out the language was a deliberate attempt to wipe out the culture and with it the connections to communities and landscapes. It has left a huge gap in people's lives that still has social implications.

One of the readers who nominated Norman's poem for the Poetry Archive commented that - "I too have often felt isolated from my own heritage. As I don't speak the native language of my homeland, I can only learn about the origins of my culture from what I can see. Language is so integral to culture that it almost impossible to understand a culture without understanding the language – especially when that culture is based upon an oral tradition."

Gordon Brown once quoted from one of Norman's poems 'Praise of a Man' in a eulogy he gave for a friend. The last lines could serve equally as a eulogy for the poet.

'He's gone:

but you can see

his tracks still, in the snow of the world.'

Norman MacCaig; 1910 -1996

Scottish Poetry Library

This is one of the most beautiful pieces I scribbled today. :)

ReplyDeleteThank you Jonathan.

DeleteThank you for this introduction to Norman MacCaig. I am enjoying your blog and will poke around further.

ReplyDelete